- Grip with dominant hand.

- Apply maximum force while arm is straight in front of the body.

- Repeat three times while non-participant records the maximum force reading.

Health, training and exercise

Chapter 1

Health, fitness and exercise are essential to the sporting and life performance of humans. The relationship between the three is cyclical.

Exercise can be defined as “a form of physical exercise done to improve health or fitness, or both”. It is recommended that adults and children follow different activity routines in order to maintain good health and fitness:

Adults: five sessions of thirty minutes activity per week. The activity should be physical enough to cause the adult to breathe more deeply and to begin to sweat.

Children: seven sessions of sixty minutes per week. At least two of these sessions should be of high intensity exercise such as running, jumping or sport. The seven hours may be spread out over the course of a week.

In this context, it becomes essential that physical exercise is built into the structure of the typical day. Good examples of this could be walking or cycling together to work or to school, taking part in games together in the back garden and participating in active experiences at the weekend, such as walking in the countryside or going for a bike ride. Children learn a great deal from their parents and therefore it is important that parents present active role models and opportunities for their children.

It is estimated a lack of exercise is responsible for about 5.3 million deaths a year worldwide – about the same number as smoking.

This is based on estimates of the impact on inactivity on coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes and two specific cancers – breast and bowel – where lack of exercise is a major risk factor. High blood pressure and the narrowing of the arteries are also consequences of a sedentary lifestyle.

Can an athlete be fit but not healthy?

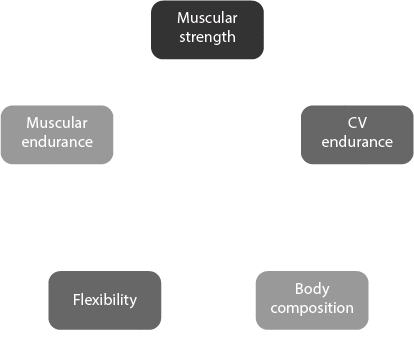

Fitness can be broken down into different components or parts.

These subdivisions make it easier to understand fitness and also to understand the different requirements of sporting activities and the different roles within the same activity.

For example, if we look at the game of field hockey. The top three fitness requirements of the goalkeeper and the midfielder might look like this:

It is obvious that the training for these two performers must be completely different and must focus on the specific requirements of the individual position.

Health-related components

| Health-related component | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Body composition | The percentage of body weight which is fat, muscle and bone | The gymnast has a lean body composition to allow them to propel through the air when performing on the asymmetrical bars |

| Cardiovascular fitness | The ability of the heart, lungs and blood to transport oxygen | Completing a half marathon with consistent split times across all parts of the run |

| Flexibility | The range of motion (ROM) at a joint | A gymnast training to increase hip mobility to improve the quality of their split leap on the beam |

| Muscular endurance | The ability to use voluntary muscles repeatedly without tiring | A rower repeatedly pulling their oar against the water to propel the boat towards the line |

| Muscular strength | The amount of force a muscle can exert against a resistance | Pushing with all one’s force in a rugby scrum against the resistance of the opposition pack |

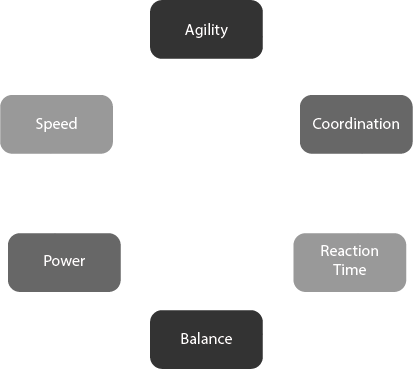

Skill-related components

| Skill-related components | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Agility | The ability to change the position of the body quickly and control the movement | A badminton player moving around the court from back to front and side to side at high speed and efficiency |

| Balance | The ability to maintain the body’s centre of mass above the base of support | A sprinter holds a perfectly still sprint start position and is ready to go into action as soon as the gun sounds |

| Coordination | The ability to use two or more body parts together | A trampolinist timing their arm and leg movements to perform the perfect tuck somersault |

| Power | The ability to perform strength performances quickly | A javelin thrower applies great force to the spear while moving their arm rapidly forward |

| Reaction time | The time taken to respond to a stimulus | A boxer perceives a punch from their left and rapidly moves their head to avoid being struck |

| Speed | The ability to put body parts into motion quickly | A tennis player moving forward from the baseline quickly to reach a drop shot close to the net |

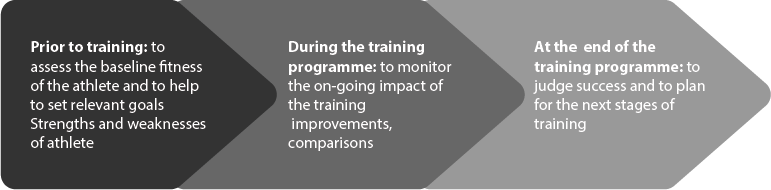

Fitness testing is a central and essential feature of all fitness training and will be used before training begins, during the training programme and again at the end of the training programme.

Here are some of the most popular methods of testing each component of fitness with a short description of the protocol for each one.

Screening is a way of finding out if people are at risk prior to an exercise programme. Screening can take the form of a questionnaire or a heart rate, blood pressure or breathing test.

With all of these tests, it is essential to judge both the validity and reliability of the process. Validity refers to the test measuring what is claimed to measure. It is difficult to justify whether the handgrip dynamometer test measures whole body strength rather than just arm strength. Likewise, the multi-stage fitness test is a more appropriate test for distance runners compared to swimmers or cyclists.

Reliability requires that the test should produce similar results each time the test is taken, unless there has been a significant change in the fitness level of the participant. It is essential that fitness tests be completed with the scientific rigour found in experimental practices, especially with regard to the accuracy of timing and measurement.

All of the tests provide data which can be compared to normative scores. These normative scores are indicators of how the participant has performed in comparison to the general population. Fitness tests are only relevant when the scores are compared to normative data. However, highly trained athletes may find that normative comparisons are no longer relevant to their own progress. An athlete such as Katarina Johnson-Thompson will only be interested in how her fitness data compares to other athletes and specifically to her own previous fitness test performances. As a result, Katarina’s ongoing fitness can be tracked and action can be taken exactly when and where it is needed most.

All of the tests provide data which can be compared to normative scores. These normative scores are indicators of how the participant has performed in comparison to the general population. Fitness tests are only relevant when the scores are compared to normative data. However, highly trained athletes may find that normative comparisons are no longer relevant to their own progress. An athlete such as Katarina Johnson-Thompson will only be interested in how her fitness data compares to other athletes and specifically to her own previous fitness test performances. As a result, Katarina’s ongoing fitness can be tracked and action can be taken exactly when and where it is needed most.

The training of an athlete must be appropriate for that person and their sport in order for them to get the most out of the training.

Following these golden rules will help to guarantee success and will carry athletes towards their training and performance goals. All training is aimed at causing long-term physical changes in the bodily systems. These changes must be referred to as adaptations.

Training must be relevant to the individual and their sport. This can be achieved by tailoring training specifically for the sport or even the position that the individual plays, the muscle groups they use the most or the dominant energy system of the athlete. For example, a 100 m sprinter is likely to train very differently to a 10 km racer despite them both being track athletes. The sprinter will focus on speed and power while the distance runner will train for cardiovascular fitness and the ability to work aerobically at high intensity.

Training frequency, intensity and duration must be increased over the training period to ensure that the body is pushed beyond its normal rhythm. Increases must be gradual so that the athlete avoids a plateau in performance or, even worse, injury.

Training must be varied, this will help with progression. Variance tends to focus on different training sessions and activities still work on the specific component of fitness. It will help to avoid a plateau in performance and also reduce tedium.

All athletes are different. Training must be related to the athlete’s age and gender, their injury status and fitness level. Any training that fails to be relevant to the individual will fail to motivate the athlete and will prove to be unsuccessful in the long term.

Physical adaptations occur during the recovery and non-active period of the training cycle. Athletes and trainers must therefore achieve the right amount of rest between sessions, good sleep patterns and the right nutrition, including the use of protein, to help repair the damage caused by intense training.

Systems reverse or de-adapt if training stops or is significantly reduced, or if injury prevents training from taking place. It is essential to avoid breaks in training and to maintain the motivation of the athlete.

Training is effective when it specifically targets the individual athlete. One way of achieving this is by targeting the most relevant training threshold. For many athletes this involves calculating a specific working heart rate:

Maximum heart rate = 220 – age

A 20-year-old athlete might want to calculate their maximum heart rate in order to accurately calculate their training threshold:

Maximum heart rate = 220 – 20

Maximum heart rate = 200 beats per minute (bpm)

Once we have calculated the maximum heart rate, we can calculate the training thresholds.

Example 1: A 20-year-old distance runner wants to calculate working intensity within the aerobic zone:

Maximum heart rate = 200

Lower training threshold of the aerobic zone = 60% of maxHR

Lower training threshold = 0.6 × 200

Lower training threshold = 120 bpm

Upper training threshold of the aerobic zone = 80% maxHR

Upper training threshold = 0.8 × 200

Upper training threshold = 160 bpm

Therefore, the 20-year-old aerobic athlete needs to target their training between 120–160 bpm to make the training effective.

Example 2: A 35-year-old basketball player wants to calculate working intensity within the anaerobic zone:

Maximum heart rate = 185

Lower training threshold of the anaerobic zone = 80% of maxHR

Lower training threshold = 0.8 × 185

Lower training threshold = 148 bpm

Upper training threshold of the anaerobic zone = 90% maxHR

Upper training threshold = 0.9 × 185

Upper training threshold =167 bpm

Therefore, the 35-year-old anaerobic athlete needs to target their training between 148–167 bpm to make the training effective.

The numbers and calculations above can be replaced for any type of athlete. Highly trained athletes will tend to train nearer the upper limit of the training threshold to gain maximum benefit.

A 16-year-old elite level triple jumper training to improve athletic performance. They have a specific goal of being selected by county for the next athletics national championships.

Specificity – training would be focused on explosive strength of the legs by using weights and plyometric training. As long jumpers need to be highly flexible, a significant amount of time would be given to increasing flexibility through stretching.

Progressive overload and FITT – training frequency would be approximately 6 times per week. Training intensity would be increased gradually by increasing the weight lifted and then increasing the target heart rate range in interval sessions. Time can be progressively overloaded by decreasing recovery times in weight training and increasing the numbers of repetitions during plyometric training. Training type can be varied by combining weight, plyometric, interval and flexibility training.

Individual difference – this athlete is at optimal training age for strength gains and every effort should be made to cause adaptations in the body. However, there must be enough variety and rest in the training to ensure the athlete does not burn-out or become injured. Training six times a week also requires the athlete to have fun and enjoy the training.

Rest and recovery – the long jumper only has one full rest day each week, so training units (sessions) need to be structured to allow for muscle groups to rest and recover. An example of this would be to use a flexibility session the day after a heavy weights and plyometrics day. Likewise, the training could be structured so that the athlete works the upper body the day after training the lower body, thus allowing the legs to rest.

Reversibility – the long jumper is training six times per week. Injury and burn-out are avoided by allowing for recovery and providing varied types of training. This should prevent de-adaptation. Injury must be avoided at all costs.

A 16-year-old road cyclist training to achieve their first race in a national team. The rider is a specialist hill climber.

Specificity – training would be focused on cardiovascular fitness through a process of continuous training with other anaerobic methods used to improve the hill climbing. Training would take place for long periods to prepare the athlete for the full day cycling required by elite road cyclists.

Progressive overload and FITT – training frequency would be approximately six times per week. Training intensity would be increased gradually by increasing the target heart rate range in continuous sessions. Time can be progressively overloaded by increasing the length of sessions and the proportion of the session spent climbing. Training type can be varied by combining continuous, interval and flexibility training.

Individual difference – this athlete is young and every effort must be made to ensure they make fitness gains without causing injury through overtraining. Training must be varied to prevent boredom or burn-out.

Rest and recovery – the cyclist only has one full rest day each week, so training units (sessions) need to vary in terms of length and intensity. Successive high intensity hill sessions should be avoided. Recovery must be optimised through the use of effective cool downs as well as excellent nutrition between sessions.

Reversibility – the cyclist is training six times per week during in-season training. Attention must be given to ensuring that over-use injuries do not occur by recovering properly from training and by using good nutrition.

There are a number of different ways of training that can improve health and fitness necessary for a range of activities. Warming up and cooling down is essential for all training sessions.

Training should be considered to be a very deliberate and controlled process following precise guidelines. One of those guidelines is that every session starts with a warm up and ends with a cool down. Specific training methods are used to bring about specific outcomes and even the timing and order of when to use each training method can be planned to the finest detail.

The illustration shows the three primary components of an effective warm up. All warm ups should last a minimum of ten minutes and typically are much longer.

The illustration shows the three primary components of an effective cool down. Athletes always cool down following training and performance.

Ice baths and massage are techniques that are also used to speed up the recovery process.

All methods of training need to be specific to the individual performer, component of fitness and the activity.

The energy balance equation is the relationship between the energy consumed – measured in calories and the energy expended – also measured in calories. Maintaining a healthy weight requires a balance between energy in and energy out. Too much energy in or too little energy out leads to excess energy being stored as fat. Too little energy in or too much energy out leads to weight loss.

Energy in = energy out healthy weight

Energy in and energy out do not have to balance every day. The energy equation needs to balance over time for people to maintain a healthy weight.

Understanding food – knowing what makes a healthy diet helps people to manage the energy balance, and people’s levels of physical activity are as important to the energy balance as their diet.

Why is it unhealthy to regularly burn more calories than are eaten?

The body needs a balance of nutrients to stay healthy. There are five groups of nutrients.

| Nutrients | Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins | Tissue growth – known as the body’s building blocks | Animal products – meat; fish; dairy Plants – lentils; nuts; seeds |

| Carbohydrates | Source of energy. Divided into: Simple carbohydrates – sugars Complex carbohydrates – starches | Simple – sugar; glucose; fructose Complex – bread; pasta; rice; potatoes |

| Fats | Source of energy. Four types: Monounsaturated, Polyunsaturated – omega 3 and 6, Saturated fats, Trans fats | Monounsaturated – olive oil; avocados Polyunsaturated – oily fish; nuts; sunflower oil; soya beans Saturated fats – full-fat dairy; fatty meats, Trans fats – many snack foods |

| Minerals | Essential for many processes, e.g. bone growth/strength; nervous system; red blood cells; immune system. Need small amounts only | Calcium – milk; canned fish; broccoli Iron – watercress; brown rice; meat Zinc – shellfish; cheese; wheat germ Potassium – fruit; pulses; white meat |

| Vitamins | Essential for many processes, e.g. bone growth; metabolic rate; immune system; vision; nervous system. Need small amounts only | A – dairy; oily fish; yellow fruit B – vegetables; wholegrain cereals C – citrus fruit; broccoli; sprouts D – oily fish; eggs; fortified cereals |

The body needs to be hydrated to stay healthy. Failing to replace lost fluids can result in dehydration. This is a more serious condition than lack of food. Women should drink around 1.6 litres (approximately 8 glasses) of fluid per day and men should drink around 2 litres (approximately 10 glasses) of fluid per day. This varies according to the temperature and how rigorous the exercise. All drinks count but water and milk are the healthiest. Fruit juices are fine in moderation but do contain high levels of sugar.

Fibre is an important part of a healthy diet. It is only found in plant-based foods. There are two types of fibre and each one helps the body in different ways:

A balanced diet is the starting point for most people but sportspeople may have specific dietary needs. This reflects their personal energy balance equation. When people become more active they use up more energy so they need to take in more to restore their energy balance. Athletes adjust their diets differently depending upon their sport and training/performance schedule.

On average, men need around 2,500 calories a day while women need around 2,000 calories. When athletes are training intensively this may increase to around 5,000 calories a day.

Eating patterns may vary according to the day’s training programme or competition schedule. For example, an elite rower may eat two breakfasts – one before and one after the first of the day’s training bouts. Tennis players often eat a banana between games during a long match. Generally, performers do not eat two hours before, or after, performing.

Carbohydrates provide energy. The complex carbohydrates – starches – are stored in the body as glycogen and converted into glucose when the body needs more energy. Glycogen is a slow-release form of energy. This is particularly useful for endurance athletes in the last stages of a performance. So, for example, in the week leading up to a race, marathon runners may eat lots of starchy foods, such as pasta. This helps them to keep going towards the end of the race.

Protein builds tissue, including muscle. Athletes who want to build up their muscle during strength-training sometimes eat high-protein diets. This includes obvious strength-training athletes, such as weightlifters, but also includes endurance athletes who want to repair or prevent torn muscle. The value of high-protein diets is debatable. Athletes do not need much more protein than other people; protein is difficult to digest and it does not automatically turn into muscle – the athlete still needs to do strength-training, which is fuelled by carbohydrates.

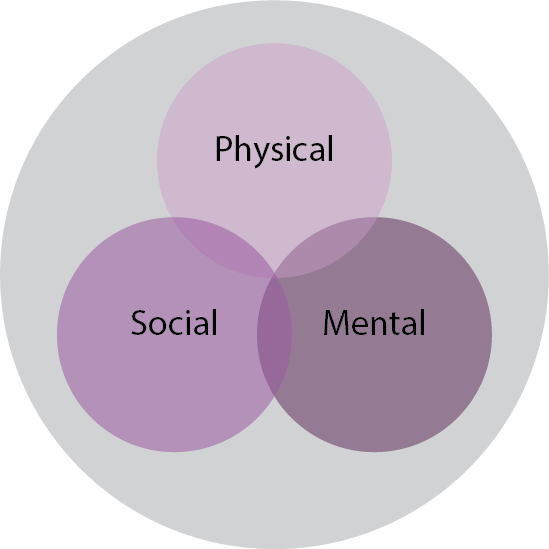

Physical activity is an essential part of a healthy lifestyle. Linked to other positive lifestyle choices, it promotes good physical health and contributes to people’s mental and social well-being.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”.

Good physical health is linked to fitness – being able to perform effectively the physical tasks involved in life as well as sport. Being physically healthy includes:

Emotional or mental health is linked to personal well-being – feeling positive about yourself. Being emotionally healthy includes:

Social health also contributes to well-being – feeling positive about interactions with other people and the wider world. Being socially healthy includes:

Feeling anxious and stressed often is an indication of which type of poor health – physical, emotional or social?

Positive lifestyle choices include:

A healthy lifestyle offers two types of benefits – what people want to gain; for example, happiness; as well as what people want to prevent; for example, having Type 2 diabetes. People are often more motivated by gain rather than prevention. Benefits may be immediate and long-term.

Making negative lifestyle choices can be active (something people do) or passive (something people choose not, or neglect, to do). They include:

A negative lifestyle affects the body and mind. The negative effects can be short-term and long-term. They may also affect others, for example, someone’s children. Generally, people are more motivated to change their behaviour to gain positive benefits than to avoid negative effects, especially when the negative effects may not appear until far into the future.

What are some of the common long-term effects of eating too much fat, sugar and salt?

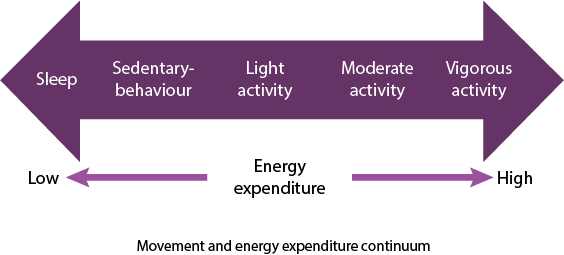

People should meet nationally recommended levels of weekly physical activity as part of a healthy lifestyle. They also need to reduce the amount of time they are sedentary.

In the UK, the four home countries’ chief medical officers have issued guidelines for how much physical activity people should do. This is a simplified version of the recommended levels of physical activity:

| Age group | Amount | Intensity | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infants | Not specified | Any intensity | Floor-based play; water-based play; crawling |

| Under 5s – walking | At least 180 minutes spread across the day | Light or energetic | Walking; skipping; climbing; chasing |

| 5–18 years | At least 60 minutes per day | Moderate to vigorous | Running; dancing; cycling; swimming; active games |

| 19–64 years | At least 150 minutes per week, e.g. 5 × 30 minutes | Moderate to vigorous | Brisk walking; cycling; swimming; gardening |

| Over 65s | At least 150 minutes per week, e.g. 5 × 30 minutes | Moderate to vigorous | Brisk walking; dancing; climbing stairs; tai chi |

Moderate intensity activity – makes someone breathe harder, feel warmer and their heart beat more rapidly but they should still be able to hold a conversation.

Vigorous intensity activity – makes them breathe much harder, feel hotter and their heart beat much more rapidly so they will find it more difficult to hold a conversation.

This will depend on the individual’s current level of fitness as well as the type and duration of physical activity. Any physical activity is better than none!

In 2015, 79% of boys and 84% of girls aged 5–15 years in England did not meet the physical activity recommendations (Public Health England).

Does walking, cycling or scooting to school count towards a child’s daily physical activity target?

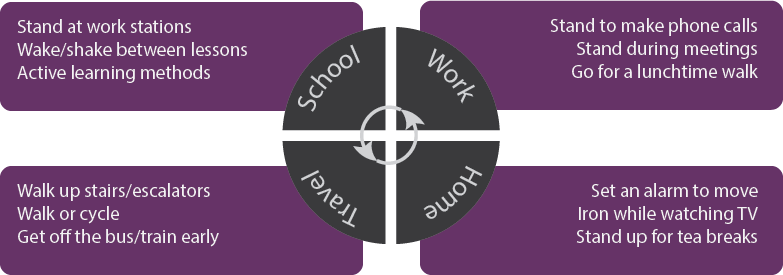

In addition to the recommended levels of physical activity, people also need to reduce sedentary behaviours. Being sedentary means sitting or lying down for extended periods of time when awake.

Sedentary behaviours include:

People are more sedentary now than in the past due to changes to our general lifestyle. For example, fewer people have manual jobs, more people own cars and drive, and technology has affected almost everything from housework to leisure.

People’s risk of developing some health conditions, such as Type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease, increases if they have a sedentary lifestyle. Recent research suggests that a sedentary lifestyle can be harmful even if a person meets the recommended levels of physical activity.

Changing sedentary behaviours means altering many, often small, aspects of people’s daily lives.

These case studies highlight some of the challenges people face in their daily lives if they are to become more physically active and reduce sedentary behaviours.

What two things could you do at school to reduce the time you spend being sedentary?