Sight – a curler pictures where the curling stone will stop

Psychology of sport

Chapter 4

The majority of sports require key characteristics to achieve a skilled performance. Skills are learned abilities that athletes acquire through training and practice. Skill may be defined as the ability to perform at a high standard effectively and efficiently.

When watching a performer or performance, a skilled performance can be identified when demonstrating the following characteristics:

Effectiveness

Efficiency

Responsive

Skills are not easily identified and are therefore placed along continuums.

A continuum is a range or sliding scale between two extreme points. Each point on a continuum is slightly greater or smaller than its neighbours. You can move up or down a continuum

For example, in physical education (PE) pupils take part in a games continuum based on their age:

Sports skills are arranged on different continuums. These are:

Skills affected by the environment are called open skills. They occur when performers have to adapt their skills to a changing or unpredictable environment.

Examples of environmental stimuli (or variables) are:

Performers need to have a good perception of these stimuli to adapt their skills to suit the environment.

Skills that are not affected by the environment are called closed skills. They occur in constant or predictable situations where the performer is in complete control of their performance, for example, a gymnast performing a floor routine.

Skills also range between open and closed. They are on the environmental continuum between open and closed skills.

A diver is in complete control

A wheelchair racer needs to be aware of racers in other lanes and adapt to the track conditions

A basketballer must react to the ball, their team and the opposition – all at once

There are two types of practice that support the development of open and closed skills:

Fixed practice (drills) involves repeating the practice and doing the same movement over and over again. This practice is best with closed skills; for example, diving.

Varied practice involves repeating the skill in a variety of situations which best suits the development of open skills; for example, catching the ball with opposition. pressurising it different situations and positions on the court or field.

Skills range according to how difficult they are to learn and perform.

Basic skills (simple skills) are simple and straightforward. They do not include complicated movements. Basic skills are often generic to many sports. Sportspeople need to master basic skills before they attempt more complex skills. Examples of basic skills include running; jumping; throwing; catching and striking.

Complex skills are more difficult. They include complicated movements that require high levels of coordination and control. They are usually sport-specific. Examples of complex skills include serving in tennis; throwing the discus in athletics and performing a vault in gymnastics.

Sportspeople also use mental skills when they perform. These include skills such as interpretation, making judgements and decision-making. Skills become more complex when they involve more interpretation, judgement and decision-making. For example, in cricket a bowler has to judge when and how often to use a reverse swing-bowling action as well as be able to do it.

Skills also range between basic and complex. They are on the complexity continuum between basic and complex skills.

Running with the ball in rugby union is a fairly basic skill

Kicking a penalty or conversion is more complex

Being able to scrum safely and effectively is a complex skill requiring multiple judgements and decisions

Skills range according to who controls the speed of the movement.

Self-paced skills (internal) are controlled by the performer. The performer decides on when to execute the skill – for example, when throwing the javelin in athletics, or when vaulting in gymnastics. These skills tend to be more towards the closed end of the environmental continuum.

External paced skills are controlled by the environment. They include decision-making and reaction. In most cases the opponent controls the rate of performance. For example, in football the defender closes down the centre forward, and this causes a decision to be made of either shooting or passing. Therefore, these skills tend to be towards the open end of the environmental continuum.

Sprinters try to block out all environmental information when they run

The goalkeeper focuses on the flight of the ball and responds accordingly

Performers need guidance to acquire and improve skills. Visual, verbal, manual and mechanical guidance are used in different situations and stages to support performers’ different learning styles.

Visual guidance is when a performer can see the skill being performed or practised. For example:

Visual guidance can show the skill as a whole movement, broken down into steps or applied within a real situation.

Many coaches and performers use technology to provide visual guidance – before, during or after practice and performance.

This type of guidance helps learners who are at the early stages of learning, who have never seen or experienced the skill before or for skilled performers who need to refine specific elements.

British Cycling uses visual guidance technology – Dartfish software – to support British cyclists to improve. The StroMotion feature breaks down complex skills into a series of static moments. Cyclists can record and playback their best performances to see when skills were being performed most effectively. In addition, the Simulcam allows them to overlay two performances to compare them. They can compare their own performances or compare themselves to their opponents.

Verbal guidance is when a performer is told how to perform a skill, what went well during their performance or how to improve next time. For example:

Feedback needs to be constructive to help the performer to improve their skills. It also needs to be specific and accurate so the performer knows exactly what and how to improve. This requires coaches and athletes to understand and use the same language and terminology.

Verbal guidance may be given before, during or after practice and performance.

This type of feedback helps learners to progress through the stages of learning and is specifically helpful in developing and refining skills

| Unhelpful feedback | Constructive feedback |

|---|---|

| You need to pass the ball better next time. | When you do a chest pass, you need to open your fingers wider to have more power and control. |

Manual guidance is when a performer is physically guided or supported by the coach. For example, manual guidance is provided when a coach guides an athlete’s arm to mimic a javelin throw or when a coach supports a gymnast to do a backflip.

Manual guidance is provided during practice rather than performance.

Coaches should always explain to performers when, how and why they need to provide manual guidance. Performers may choose not to receive manual guidance if it makes them feel uncomfortable.

This type of guidance is particularly helpful when learning a new skill at the early or later stages of learning.

The governing body of each sport provides guidelines on when and what type of manual guidance is appropriate.

Watching an elite athlete perform a skill before trying it yourself is an example of which type of guidance?

Mechanical guidance is when the performer is guided by equipment to support the learner whilst practicing the skill. The use of equipment when practicing a new skill offers safety and allows the learner to gain confidence.

The coach would use mechanical guidance at the early stage of learning in order for the learner to practice the skill safely, allowing them to get a ‘feel’ for the movement – for example, using a float in swimming to develop leg action and body position in front crawl.

At the autonomous stage of learning, mechanical guidance is used by the coach to allow the performer to develop complex moves – for example, practicing a double-front somersault using a hoist in trampolining.

The age and experience of a person are contributing factors to learning a new skill. The process of learning depends on the individual, and the coach will need to match the guidance and practice to the stage of learning.

The stages of learning are placed along a continuum from beginner to expert. They can be classified into three stages of learning.

Each one of the stages demonstrates different characteristics when they perform:

The performer is inconsistent and makes many mistakes. The performer requires support from the coach to show and tell them what they need to do. Demonstration and repetition is key to development at this stage. The coach will need to reinforce correct performance through positive feedback. The most appropriate practice would be the whole-part-whole method, giving the performer a sense of context before the skills are broken down.

The performer begins to understand the requirements of the skills and becomes more consistent. Within their performance there are fewer mistakes and the performer can concentrate for longer. More complex information can be processed and the performer can use internal feedback to improve further. Part practice would support this stage as it supports motivation and focuses on specific skills.

The performer is consistent and effective and they perform skills with consistency and accuracy without any effort. They are able to concentrate on complex tasks and information and are able to adapt their performance. They decide on the pace of the skill and activity and nearly always make the correct decisions. The coach can give detailed feedback and use complex video analysis to refine performance. Whole part tends to be used at this stage as it requires high attention to skills that cannot be broken down.

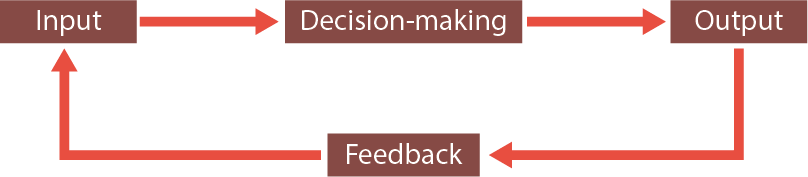

When sportspeople perform or learn and develop new skills, they have to process information. The information processing model is one method that can be used to consider how learning takes place. The model contains four parts that are linked together in a ‘learning loop’.

Input is the information that is received from the senses. At the cognitive (early) stages, this will overload the decision-making process. As the learner becomes more skilled, they selectively attend the correct cues and information.

Decision-making interprets the input using its short and long-term memory and decides what, when, where and how the learner responds.

Output is the action or actions that respond to the situation.

Feedback will indicate whether or not the response was correct and successful.

There are two types of feedback:

Intrinsic feedback is what is felt by the performer during a performance. For example, a skier may feel that they don’t have very good control of the skis when making a turn and can feel off balance.

Extrinsic feedback is provided by external sources during, or after, a performance. It includes what the performer can hear or see. For example, a wheelchair basketball player can hear verbal feedback from a coach; comments from team-mates; the response of the spectators and the referee’s decisions. The player can see where the ball goes and what is the score.

Feedback is based on two areas of knowledge:

Knowledge of results focuses on the end of the performance – for example, the performer’s score, time or position. It is sometimes called terminal feedback.

Knowledge of performance focuses on how well the athlete performed, not just the end result. For example, a golfer may have putted very well even if their drives were less effective.

Watching the monitor while on the rowing machine in the gym provides what type of feedback?

A coach will need to judge what type of feedback – intrinsic or extrinsic – is most effective in helping the performer to acquire and improve their skills. This will vary depending on the performer’s experience, ability and learning style. The following factors will help make a judgement:

| Advantages of intrinsic feedback | Advantages of extrinsic feedback |

|---|---|

| Helps performers to focus on the feel of a skill | Provides new or additional guidance |

| Helps performers to solve problems themselves | Helps performers to identify problems |

| Helps performers to develop skills independently | Offers solutions to problems |

| Gives performers more time to practise | Prevents performers from reaching a dead end |

When a performer is new to a sport, they may need more extrinsic feedback to start with. This helps them to acquire the basic skills. However, novices should also have time to practise on their own so they can begin to get a feel for and grasp those skills.

An experienced performer, who is familiar with the sport, will have acquired the basic skills. They may need more intrinsic feedback to refine and master those skills. However, experienced performers will also need extrinsic feedback to overcome persistent problems and to develop more complex skills.

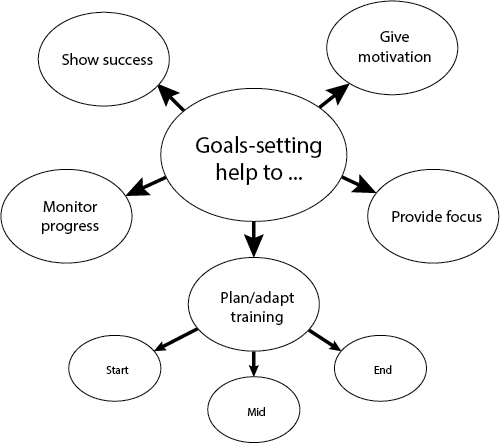

Successful sportspeople set goals to help them to focus attention and maintain motivation. Goal setting allows progress to be tracked and strategies to be used to achieve long and short-term goals.

Having goals helps participants of all abilities in physical activity and sport. They are useful for cognitive and autonomous performers, for people who take part for health and well-being and for those who are very competitive. For example, a less active person may join a gym because they want to get fit. A swimmer may aspire to take part at an elite competitive level.

Goal-setting gives:

Direction – achieving something that is really wanted

Focused effort – putting effort into achieving the goal, which provides motivation

Adherence – staying on task to achieve the goal

A goal is usually seen as the result of some endeavour. It needs to be compelling – something that someone really wants to do. It can be simple and short-term, for example, “I want to have fun in this session”. It can be about improvement over a longer period of time, for example, “I want to run a marathon”.

Goals are valuable in a number of ways:

Goals should not become expectations that weigh a person down. They can and should be adapted.

How do personal best scores help athletes to set goals?

Sometimes, people’s goals are too vague or distant. Participants lack commitment or get demotivated because their goals appear too difficult to reach. Setting targets towards a goal can make that goal seem – and be – more achievable. Targets provide focus or act as stepping stones towards the final goal.

To be effective, targets need to be SMART:

In the following example, Person A’s target is to be fit and Person B’s target is to compete at the Paralympics.

| Goal | Person A | Person B |

|---|---|---|

| S | I will increase how much exercise I do. | I will attend a Para-swimming talent identification day. |

| M | I will do an average of 60 minutes of moderate intensity activity a day. | I will swim the 50 m freestyle in under one minute. |

| A | I can see myself doing it/I’m going to do it with a friend. | My times are close to the selection criteria/my coach and I agree. |

| R | I can do it by walking daily and going to the gym twice a week/I have made a timetable. | I can do it by improving my technique/I have written it into my performance diary. |

| T | I will achieve my target by the end of this summer term. | I will attend next year’s talent identification day. |

To succeed, athletes need to prepare their minds as well as their bodies. They need to be able to manage their emotions; rehearse mentally; imagine success and use simple preparation techniques.

Psychological factors are the mental factors that help, or prevent, sportspeople from being in the right 'frame of mind' to perform well.

In sport, an athlete has to want to perform and to improve their performance. Their determination to do this is called motivation. The intensity of it is called arousal.

In the run up to the Glasgow Commonwealth Games in 2014, Team Scotland focused on helping Scottish athletes to manage the additional pressure of performing in front of a home crowd. The team recognised that this could be a positive factor but that it could also raise athletes’ levels of anxiety. They used a combination of science to measure brain activity and practical, simple tools to help athletes cope. It worked! Scotland won 53 medals during the Games, compared to 26 in the 2010 Games which were held in Delhi, India.

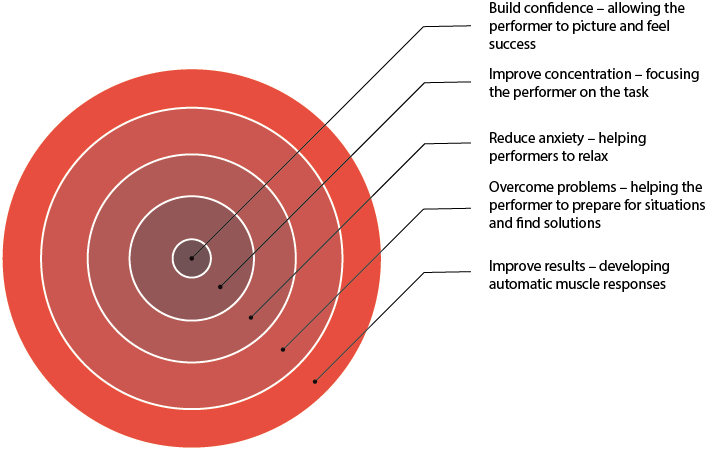

Imagery (or visualisation) and mental rehearsal can help performers to mentally prepare. They mean that performers can picture things in their mind before a performance. For example, before taking a penalty, a footballer might picture the ball hitting the back of the net.

Although we talk about picturing an image, the best use of imagery uses all of the senses. This makes the imagery more vivid. For example:

Sight – a curler pictures where the curling stone will stop

Sound – an archer hears the arrow hitting the target

Touch – a judokan feels the cloth of the opponent’s judogi

Smell – a swimmer smells the chlorine in the pool

Taste – a sailor tastes the salt in the air

Imagery and mental rehersal help performers to:

This is a combination of the performer’s determination and enthusiasm to achieve their goals and the outside factors which affect them. Motivation can take two forms – intrinsic and extrinsic.

Intrinsic motivation is the inner drive to succeed, engaging in the task or adhering to the activity for fun, enjoyment and satisfaction. An example would include going to the gym to keep healthy.

Extrinsic motivation comes from sources outside of the performer and usually involves rewards – for example, prize money; trophies; certificates or recognition.